Exhibition Essay

PATJU PRESLEY’S SOLO EXHIBITION AT VIVIEN ANDERSON GALLERY IN 2018 WAS A REVELATION. IT WAS NOT SO MUCH THAT HIS WORK HAD GONE PREVIOUSLY UNNOTICED, FOR THE PAST DECADE HE HAD BEEN SLOWLY BUILDING A FORMIDABLE REPUTATION THROUGH INCLUSION IN GROUP EXHIBITIONS. BUT IT WAS ONLY WHEN SEEN ON MASS THAT THE SUBTLE COMPLEXITY OF PATJU’S PAINTINGS BECAME TRULY APPARENT. THE EFFECT WAS LIKE A CHORUS OF VOICES COMING TOGETHER INTO THE MOST BEAUTIFUL OF HARMONIES.

Since the advent of the Aboriginal art movement, group exhibitions have tended to dominate. While this has done wonders for introducing new talent alongside established artists, it has often obscured more understated shifts in individual artist’s practices. This is particularly the case with an artist such as Patju, whose refined vision emerged almost in counterpoint to the explosive bombast of his peers at the Spinifex Arts Project. Indeed, set against the work of masters such as Fred and Ned Grant, Lawrence Pennington and Simon Hogan, Patju’s paintings are marked by a wholly different sensibility.

When these artists burst onto the scene in 1997, their work sent waves through the Aboriginal art world, in part because it seemed to signal a triumphant return to the iconographic forms that had largely slipped from desert painting as it became increasingly abstract. In Spinifex art, the classic circle- and-track forms were reinvigorated by artists working with sincerity and authority. In contrast, Patju’s work offered veils of dots, more atmosphere than icon, hovering like mist across the canvas.

While this certainly indicates Patju’s individuality as an artist, it is worth consider- ing the particular nature of this difference. Like many of his peers, Patju was displaced from his desert homelands in the middle decades of the twentieth century by Government Welfare Patrols tasked with relocating desert peoples to missions and government settlements. It was in the context of upheaval and displacement that the desert painting movement was born. It was the differing histories of people and place that created the diversity of this movement. Unlike the Rictors and the Andersons and other well-known families of the Pila Ngurru (or Spinifex People), who were moved to Cundeelee Mission, Patju and his family were picked up further north, and taken to Warburton Mission. Not long after, Patju walked the 5OO kilometers to Pukatja (Ernabella Mission) to be with family members.

If one was to draw a triangle linking Warburton, Pukatja and Tjuntjuntjara (where Patju currently lives and works) it would create an area approximately the size of Victoria. This shows the range of area that Patju covered in his youth, accounting for the vast bank of places and narratives that he has access to in his painterly repertoire.

If one was to draw a triangle linking Warburton, Pukatja and Tjuntjuntjara it would create an area approximately the size of Victoria. This shows the range of area that Patju covered in his youth, accounting for the vast bank of places and narratives that he has access to in his painterly repertoire.”

— HENRY SKERRITT

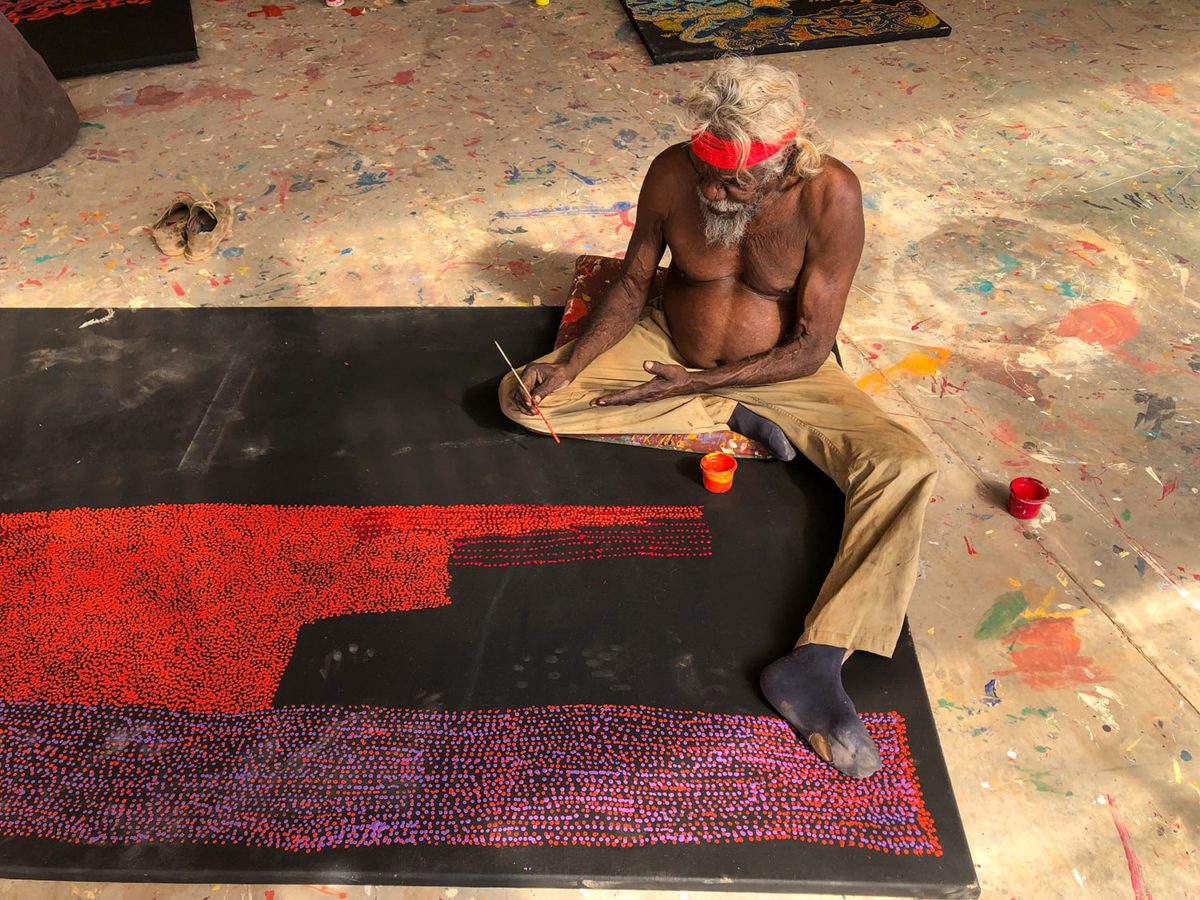

Patju Presley paints with such a spiritual confidence, as someone who knows their place in the Creation, often singing the associated songs of particular sites whilst rhythmically placing his myriad of dots.”

— SPINIFEX ARTS PROJECT

It seems the colour comes from within his being. He carries an innate optimism and gregarious positivity with a feeling that he quite possibly could ‘have it all’ and maybe he does.”

— BRIAN HALLETT

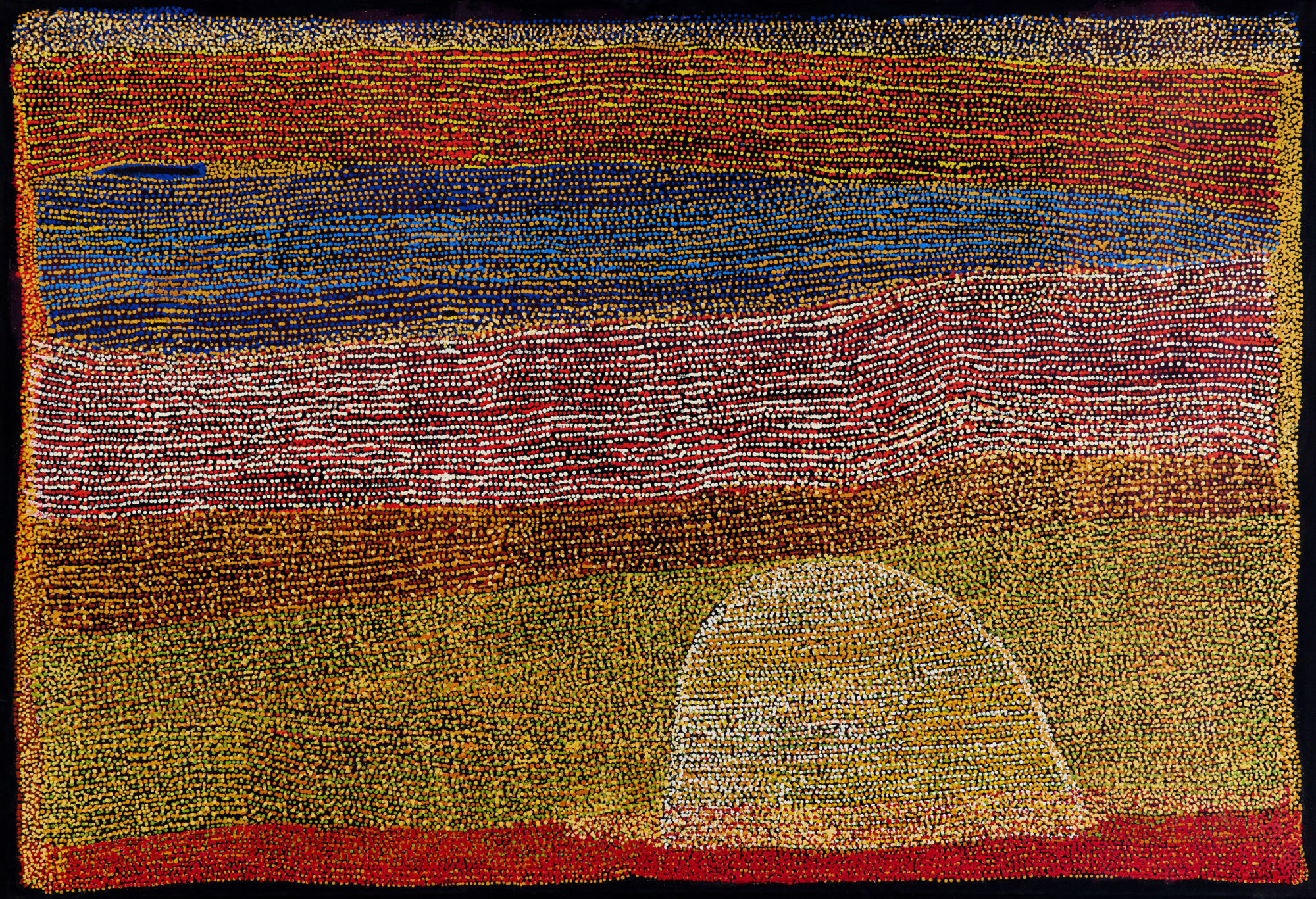

He began painting at the fledgling Irrunytju Arts where he would have encountered the work of artists such as Tommy Watson and Nyakal Dawson, with their delicate webs of flickering dots. But Patju’s early works show none of this delicacy, and while revealing flashes of brilliance, only hint at the artist he would become. Take for instance, the painting Apanyin 2OO4 in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria. It is a commanding work, but one characterized by its excess, as though Patju is using every tool in his artistic arsenal to bowl the viewer over. But there is also an awkwardness to this work, an unresolved tension between the iconic forms in the foreground and the Country they seem to float above.

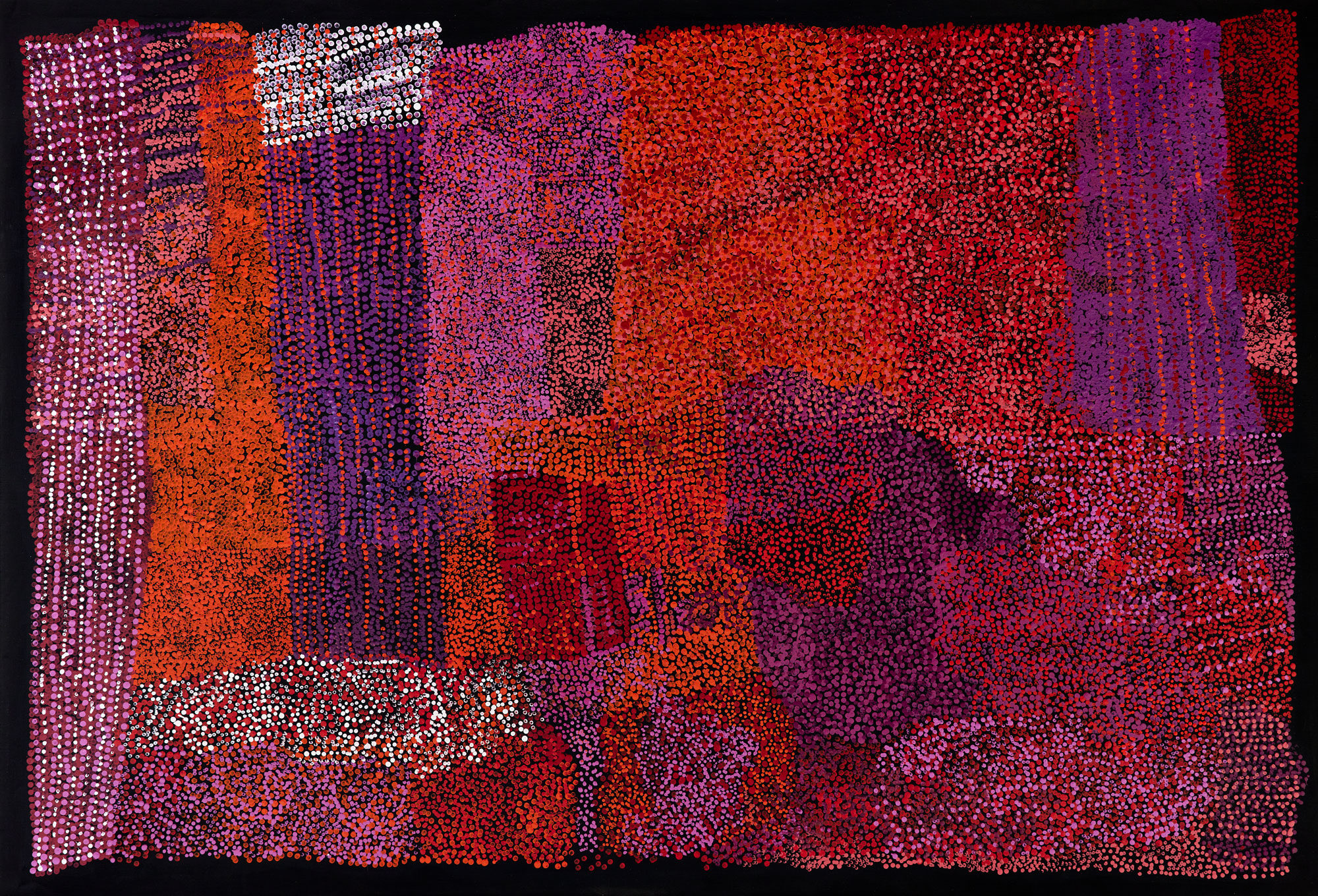

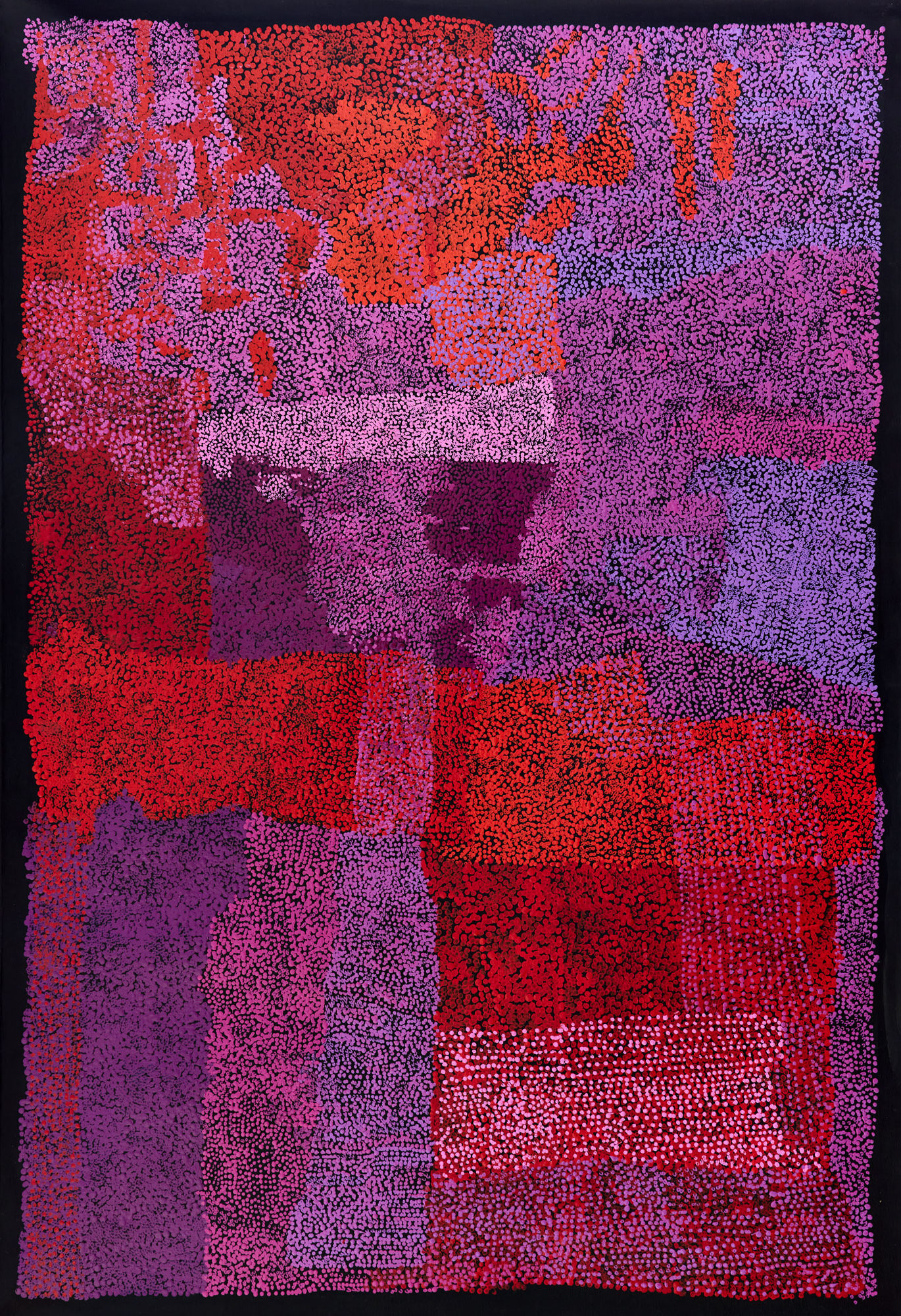

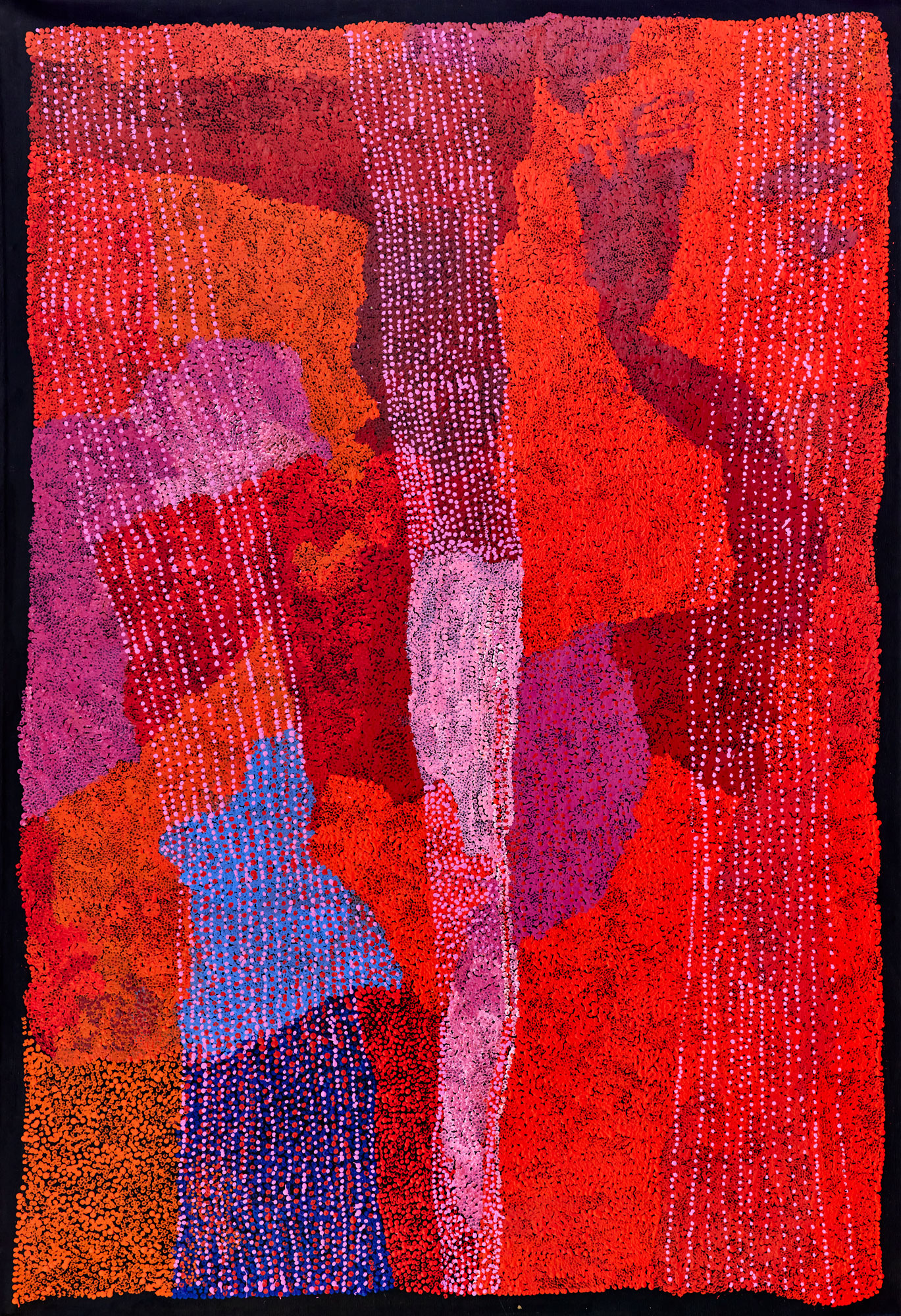

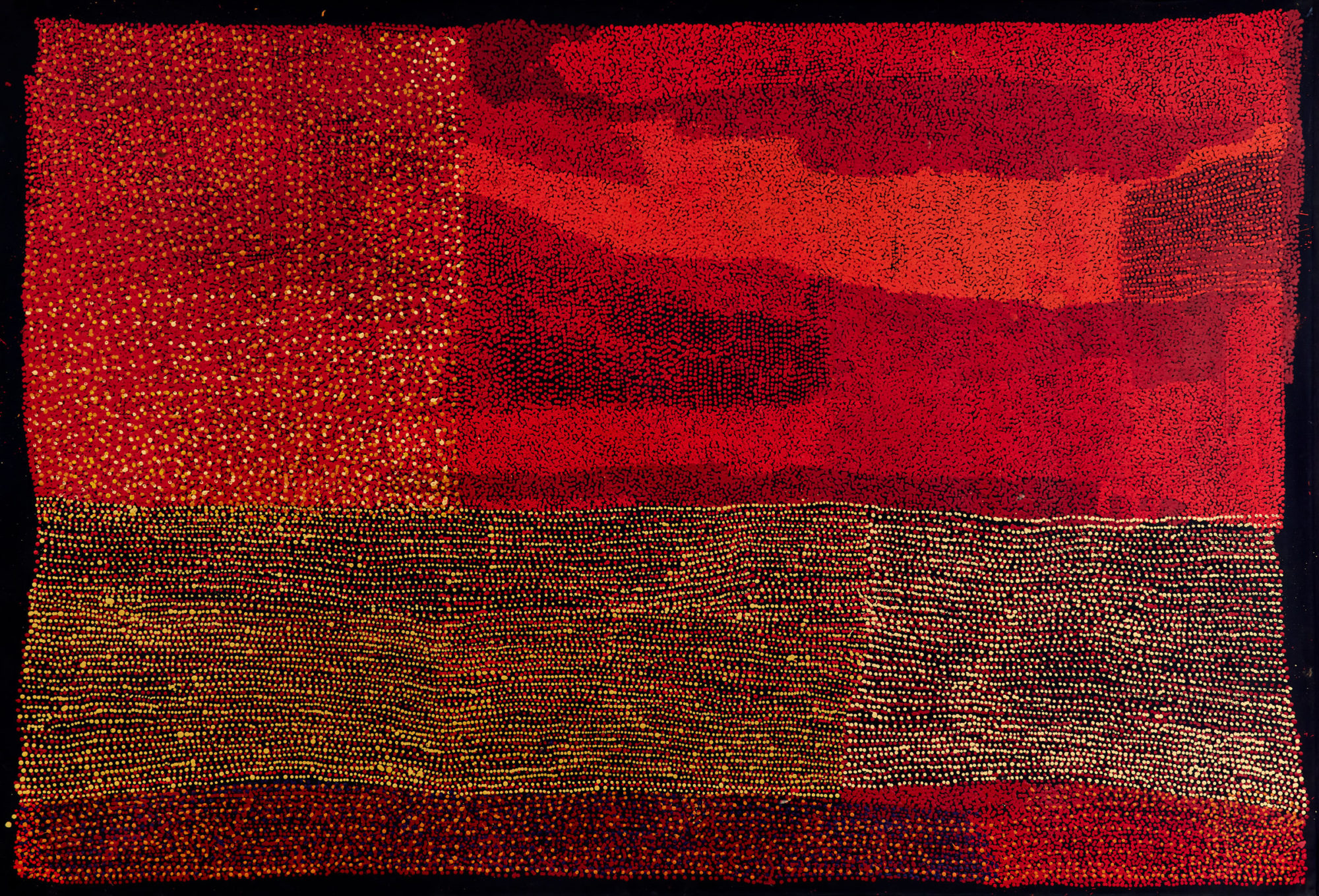

This could not be more different to works that emerged in 2O14 as Patju began painting for Spinifex Arts Project. Using nothing but fields of dots, Patju’s works for Spinifex Arts Project are characterized by their dignity, gravitas and, to a large degree, their inscrutability. Consisting of often no more than veils of dots, they are marked by a most extraordinary restraint. They are works that require patient viewing to see the subtle shifts and fleeting forms that emerge from delicate and irregular clusters of dotting.

In formalist terms, there is a classic tension in Patju’s work between what Lawrence Alloway termed “the figures and the field.” Notion being, that the most transcendent paintings were those that did not break the viewer’s experience of the sublime.

In the mid-twentieth century, this led Euro American abstract painters to an unwinnable battle with the flat plain of the canvas, leading to increasingly minimalist paintings of the 196Os. Patju is no formalist — his works maintain a clear link to the places of his ancestors. But it is a useful counterpoint in considering his development as a painter — for like the abstract painters of New York or Melbourne, faced with a similar visual (if not philosophical dilemma): namely, how much can he break the veil.

Since 2O14, this tension has animated Patju’s work in the most wonderful of ways. We have seen an artist pushing the picture plane and using delicate undulations of colour and form, to merge and weave the sections of his paintings. As these sliding tectonic plates of colour nudge, they shimmer and slide beneath each other in such unexpected and paradoxical ways that one is often left wondering if it was some kind of magic trick. This explains why it is so compelling to speak of Patju’s works in musical terms: the sections in his paintings flow across one another, more harmony than melody, their cadences leaving only a fleeting sense of form, like the impressionist melodies of Debussy.

On the one hand, it is easy to see this as a metaphor for the haptic and sensory experience of being on Country. Indeed, these works push themselves into space, their irregular black borders creating a floating sensation, as though hovering a few inches off the canvas. One might follow this logic further, to find evidence of a worldview in which ancestral presence is a constant animating force, resonating in the visual acuity of the earth. Staring at Patju’s works, I am certain there is a degree of truth to this, and yet, it is something that can be said about many of the great contemporary desert painters. Patju’s work is more unique, more individual. To explain its brilliance, it is necessary to consider his unique and specific encounters with place, art, culture and colonialism. Like all of us, Patju Presley’s experiences have shaped him and made him see the world differently to others. But it is his skill as an artist that allows him to paint this complexity, and to show us the complexity and diversity of the world we share.

HENRY SKERRITT, CURATOR

THE KLUGE-RUHE ABORIGINAL ART COLLECTION

OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA