Unvanished

2017

A SENSE OF BALANCE

Kent Morris’s family narrative, like so many Aboriginal people from the south-east, is one of separation, dispersal and suppression. The colonial project has left many shattered lives in its wake, vulnerable and searching. For many we are not the rightful inheritors of ancestral lands or vast cultural wealth but of intergenerational trauma. Coming to terms with these often-broken stories is part-and-parcel of the decolonisation practice that many contemporary practitioners such as Kent are engaged with in order to restore a sense of balance.

Kent calls Melbourne, the lands of the Boon Wurrung and Wurundjeri, home, a far cry from his Barkindji cultural homelands on the banks of the Darling River in the north-west of New South Wales. Like other displaced families, Kent’s shares a history of living in fringe camps, being moved to reserves and missions, with some eventually finding sanctuary in the big city. A product of these circumstances, Kent contends with being a responsible artist living off Country. How do Aboriginal people live and work on someone else’s country while not further contributing to colonisation? In his work Kent pays homage to the country he and his family are connected to. He listens to country and repeats what he hears. A perfect echo.

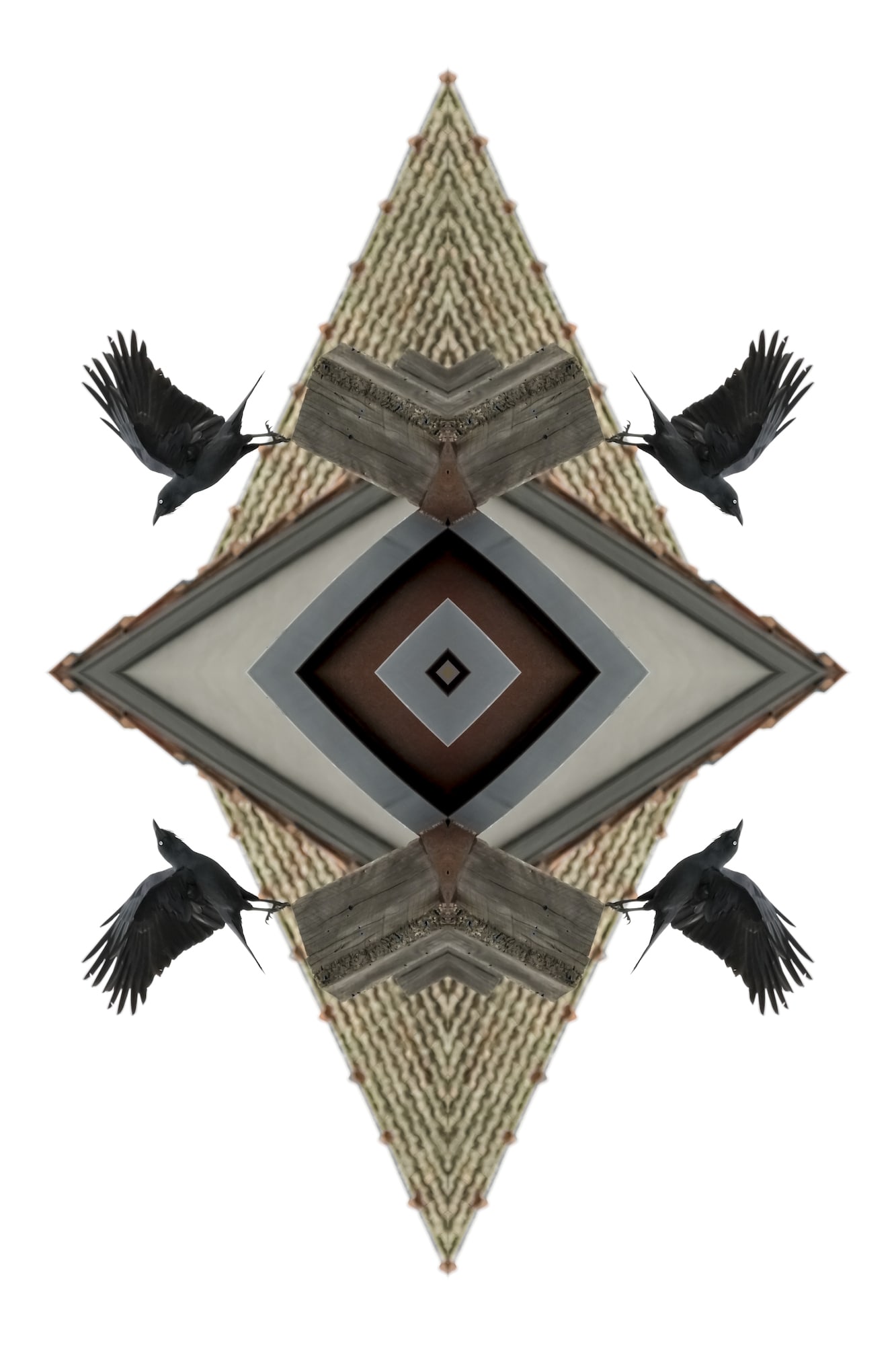

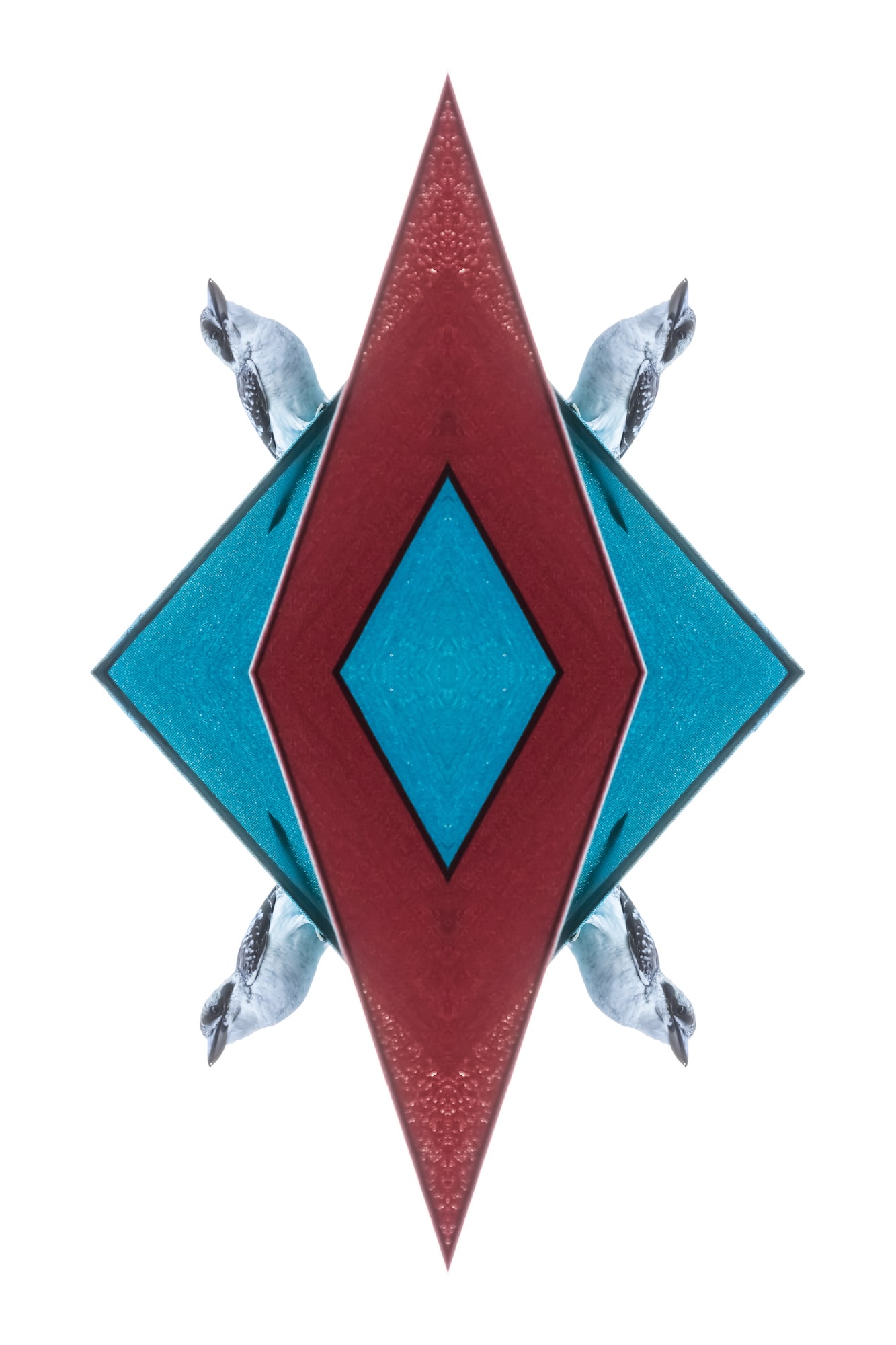

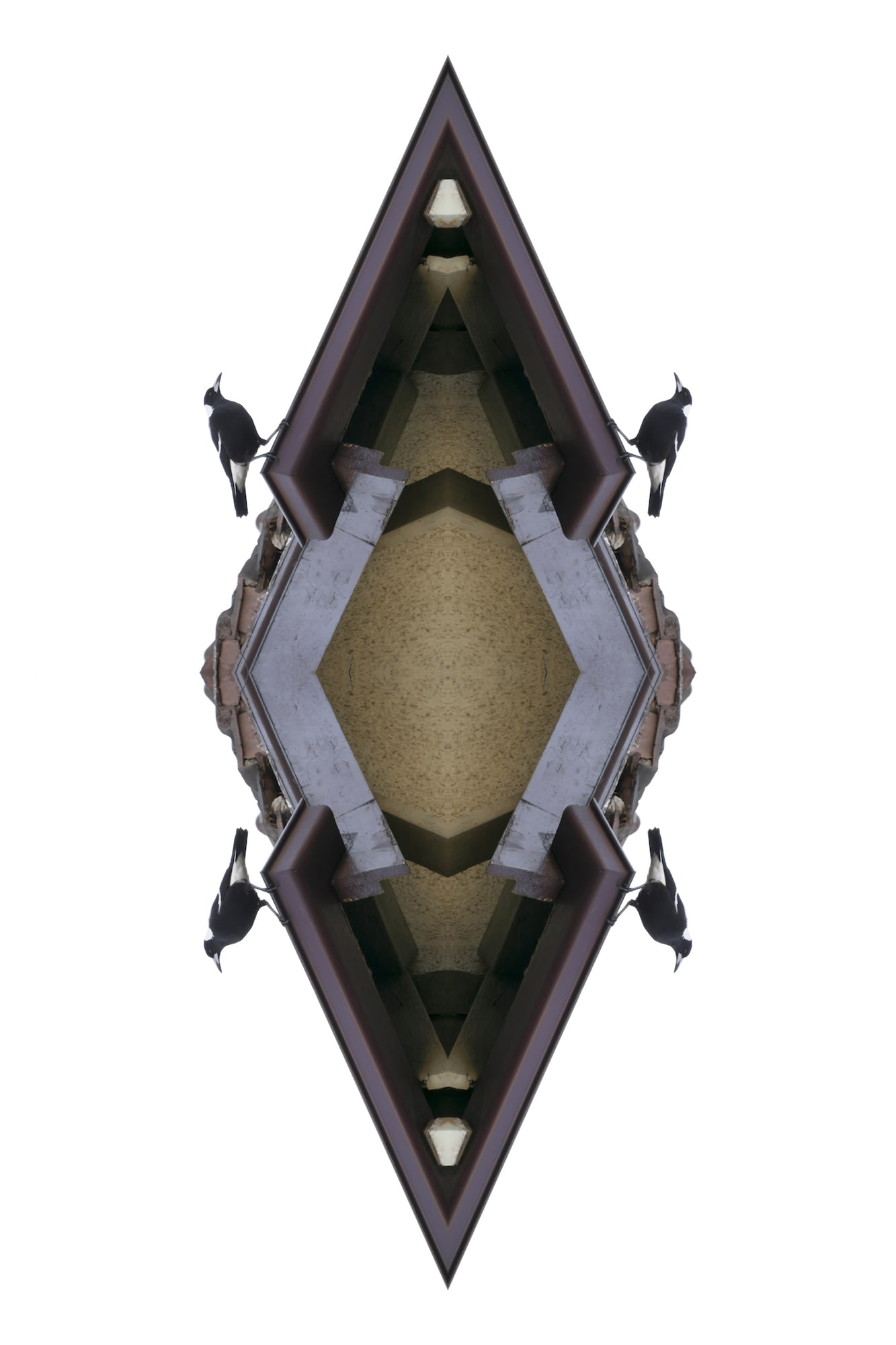

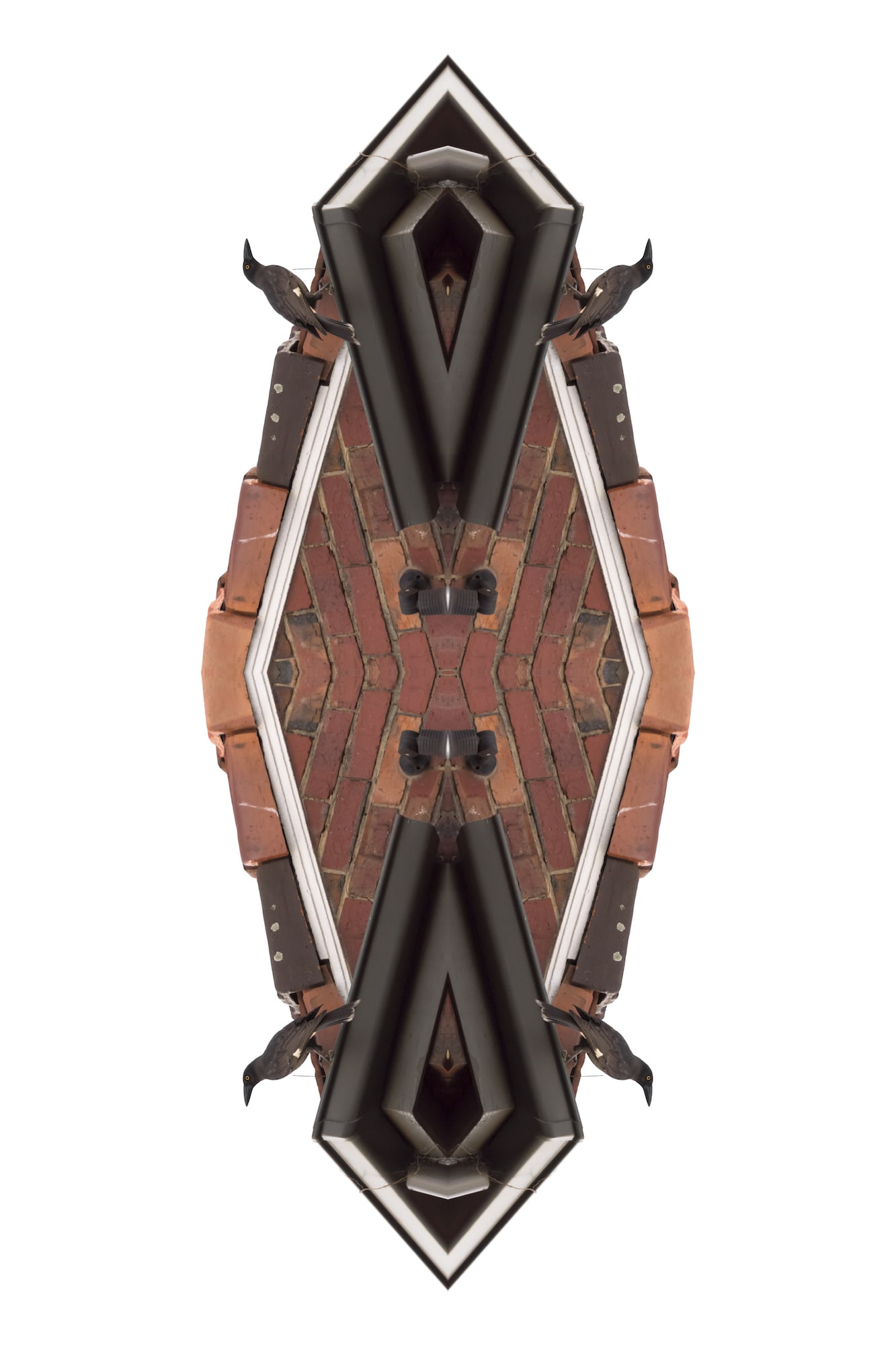

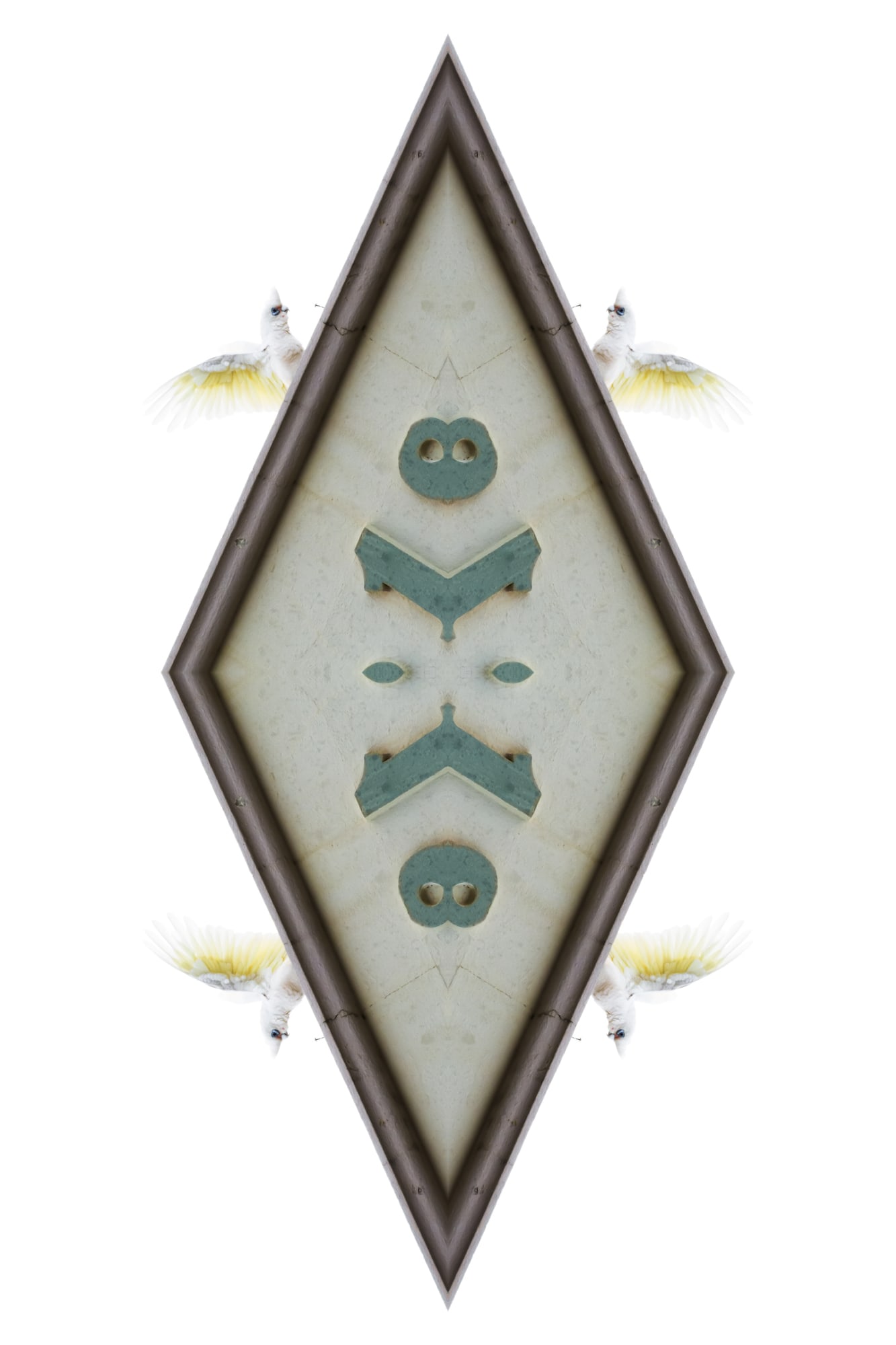

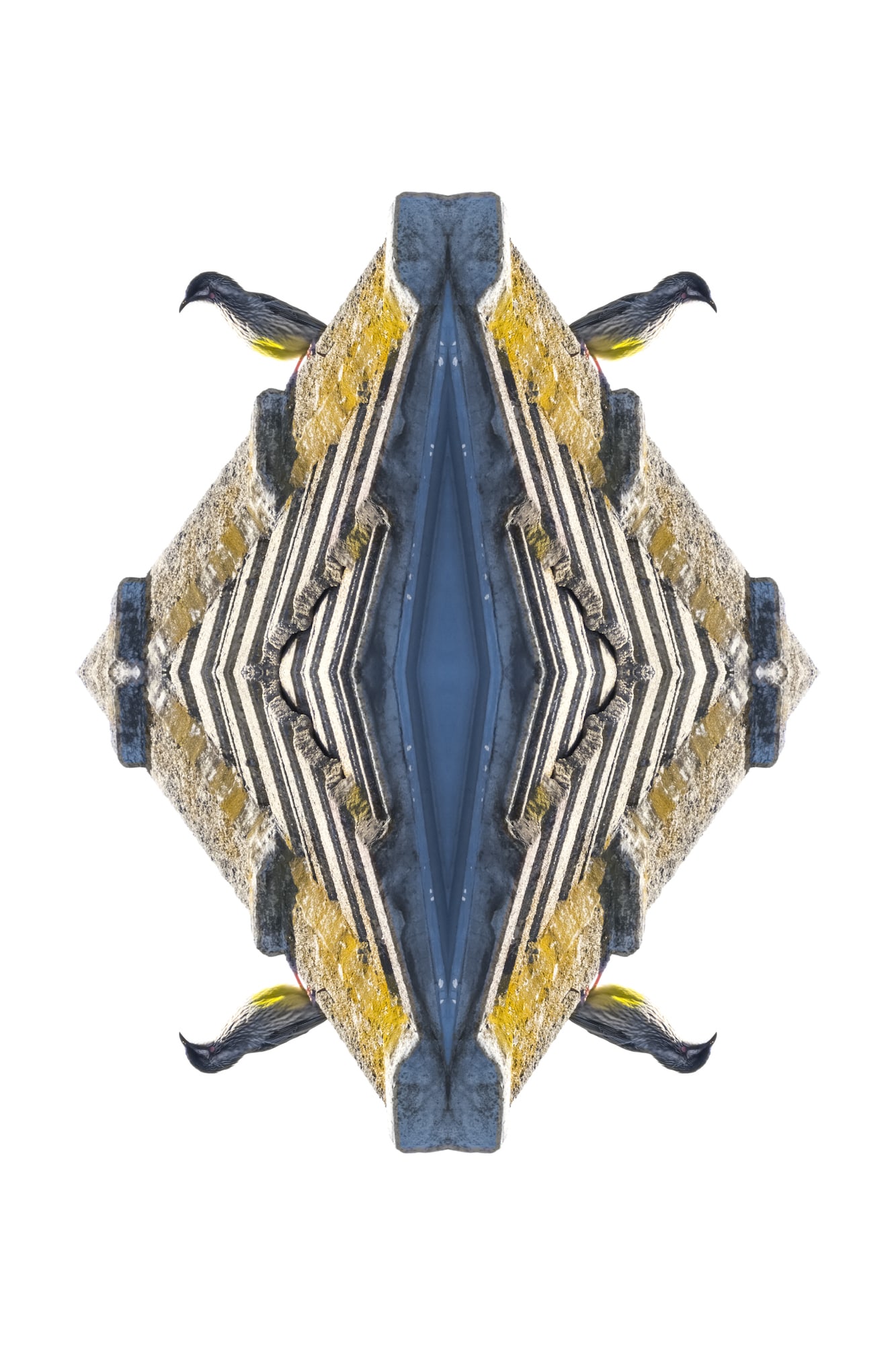

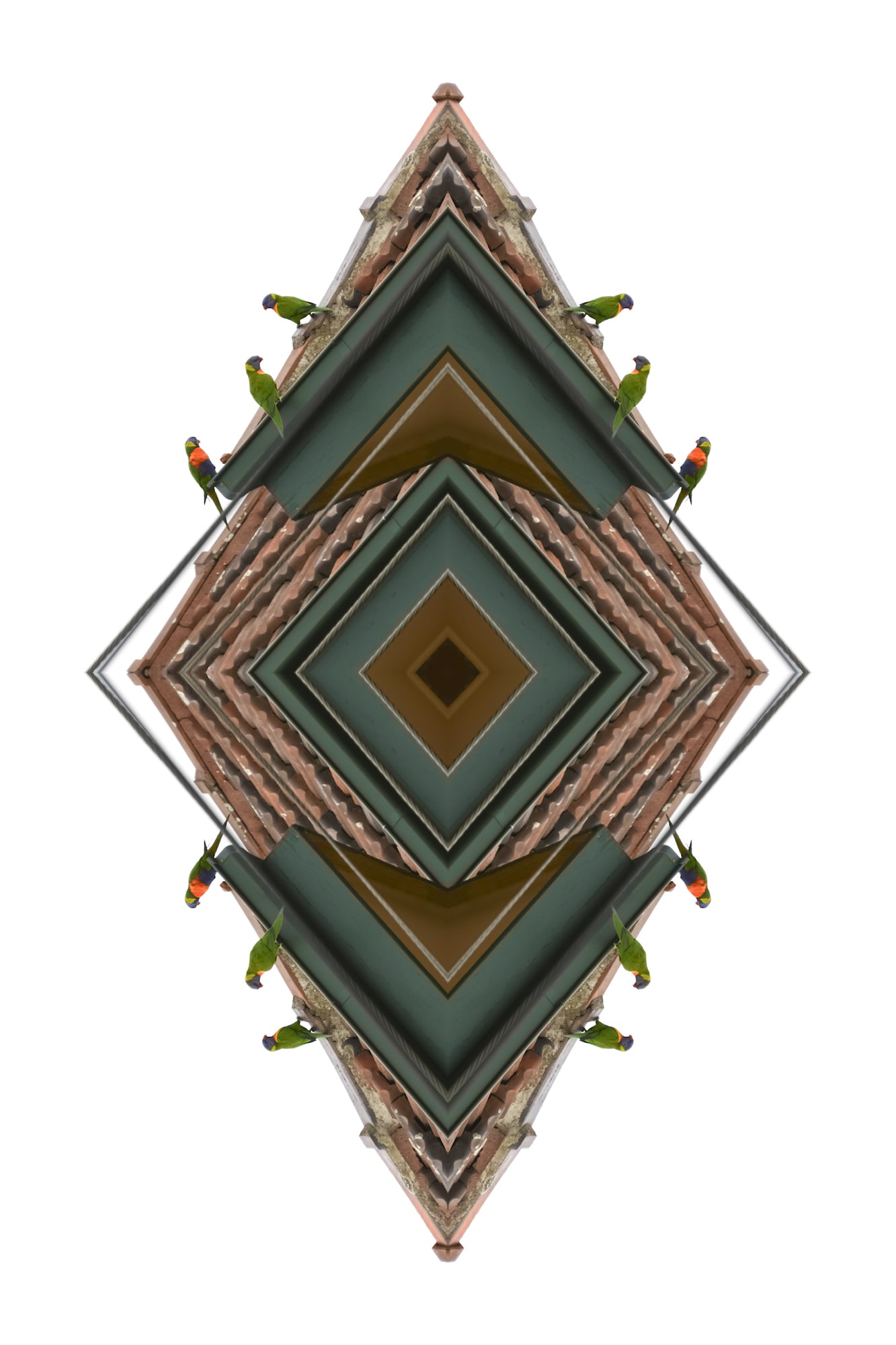

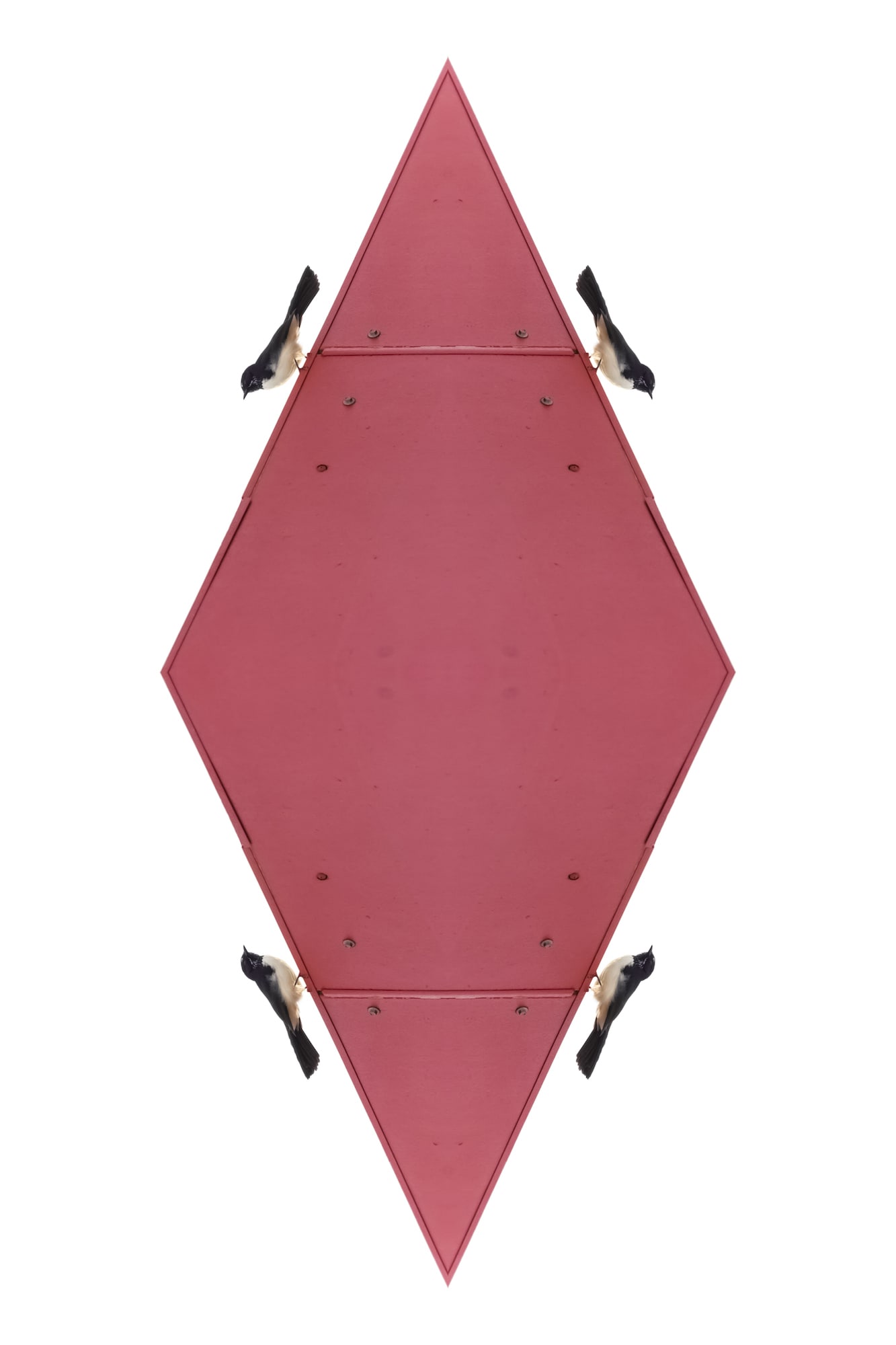

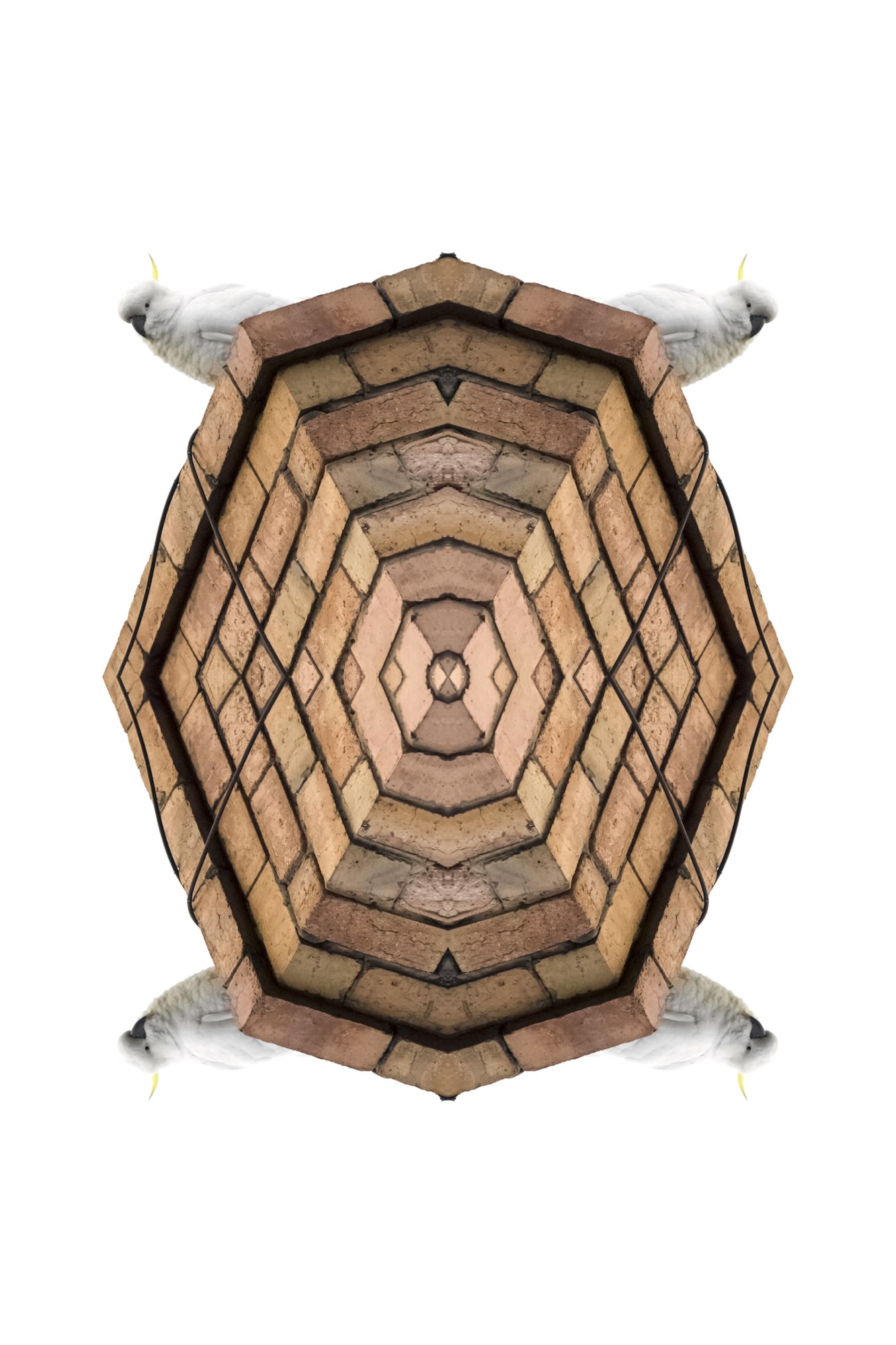

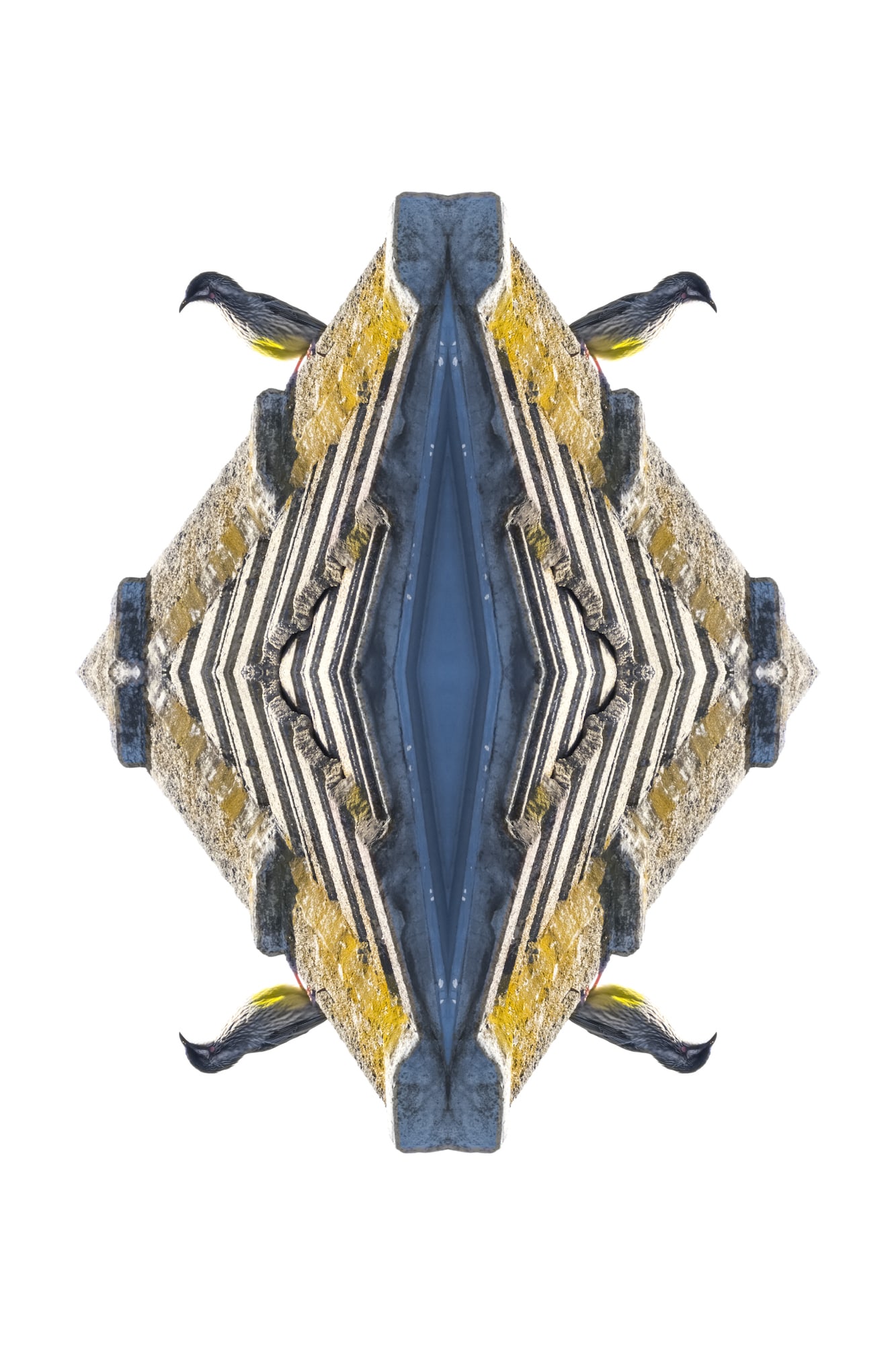

At first glance Kent’s works feel uneasy, they take their time to acquaint themselves with you. Our eyes are told to see a fore, middle and background. We search for a horizon. Although these altered worlds look manipulated, Kent often reminds us that he has done nothing to the image apart from refract it. In this process country folds in on itself, like the worked facets of a stone tool. Images that at first appear shattered are, in fact, whole.

In a world where Aboriginality is often controlled by others. Administered by others. Commented on by others. And sketched by others. Kent, in an attempt to overcome this imbalance, takes control and rebuilds a world of his own. A self-proclaimed act of empowerment. Within these re-created worlds the authority of the suburban quarter-acre block complete with a white picket fence and a Hills Hoist is broken and re-authored. Alternative perspectives are accommodated and interrelated. A utopia is sited where birds reign.

Floating like islands on a stark white background, these self-referencing landscapes give way to become objects. Their detailed surfaces, set within north-south, east-west axes, remind us of cultural objects such as shields, ceremonial boards and spearheads. Brickwork, corrugated iron and roof tiles align and shape-shift through Kent’s lens to create new forms. As both object and country, these images speak simultaneously to the dichotomy of dislocation and unification present in our everyday lives. Undercurrents, shifts and chasms are pacified. The displaced are centred.

Calling us back are the birds. To those prepared to listen they have always been our messengers. They bring hope. Creating a sense of balance and equilibrium, Kent’s works restore a shattered world and reunite us with a sense of cultural order. A kaleidoscopic effect that sees beauty in the everyday. They build bridges. Create new homes and places to perch. And as much as they envisage it, they restore a sense of harmony.

Jonathan Jones